Change Management with Table Stakes – Producing success stories that drive the effort

By Alexandra Borchardt

An excerpt from Becoming Audiences First ; Report on the first year of Table Stakes Europe

Media people accustomed to reacting to fast-paced developments can be am bivalent about plans that try to lay out every detail. Sure, structures are important. But at the same time, they need processes and tools that are highly adjustable to rapidly changing environments and less than perfect circumstances. This is where the Table Stakes methodology comes into its own.

There are project plans to die for. Full of columns, numbers, colours and dates, they seem to leave no questions open and radiate the promise of success. At least, some die-hard project management buffs might feel that way. Everybody else is less convinced. Particularly in news- rooms, where most of those involved in change management efforts are journalists, old-school project plans can scare the hell out of people. They look at the fancy tables and silently ask themselves: What if things, well... change? As journalists, they know about surprises and news developments that take unexpected turns.

The Table Stakes toolbox is derived from agile methods that originated in the software industry. Software is never perfect, there is always a beta version, and everyone works from there. The same holds for life in the newsroom – not even speaking about life in general. This is why the TS tools find acceptance among people that tend to be highly sceptical towards more orthodox management methodologies. And there is no requirement to use all of them all the time, no meticulous box-ticking needed.

These are just a couple of reasons why the Table Stakes methodology aligns so well with the thinking in the newsroom. It is plainly not true that “everyone hates change,” as often proclaimed. People hate change that doesn’t fit reality, that is conceived for its own sake, and they particularly hate change that doesn’t work because it doesn’t produce results. Then there are others who detest change because it robs them of routines and privileges they hold dear. While this can not (and should not) be avoided, there are tools to bring them around.

There’ll never be a quota of 100 percent change lovers. But the balance can be tipped so that a strong majority are in favour.

Design/do: Change is driven by small-scale success stories

The core principle that makes the methodology so usable has its origins in the software industry as well: test and experiment, in TSE lingo design and do. Change is driven by small- scale success stories that indicate what works. Even failures can be read as successes because they generate lessons. The philosophy behind this is that something like perfect doesn’t exist in rapidly changing environments. As in nature, learning and adaptation are key. Progress isn’t linear but requires constant adjustments to new circumstances. This is in contrast to old-style project planning, where progress is linear and step by step. The goals and milestones are defined in the beginning, and when they are reached, the project is done. With Table Stakes, change is never done. It is the new normal.

So what is the basic equipment needed for change made by Table Stakes, what are the tools? The first step in every transformation effort is establishing the “why” and the “what.” A proper problem definition is at the core of change. And here is the problem in the current media environment: newsrooms and their audiences are not the allies and partners they should and could be from a “journalism as a service” perspective. This is why the corresponding business relationships are underdeveloped. The same holds for advertisers and publishers. Table Stakes is all about making newsrooms and publishers “audience first” by putting quality journalism at the centre.

Understanding your problem is half the solution

To start the journey, teams have to do a thorough gap analysis. How does the publisher perform against all kinds of requirements that make an excellent audience-first-newsroom: serving audiences with the content they need on platforms they use at times they turn to them.

Clearly defining a problem within an organisation is at the core of change. And here is the problem in the current media environment: Newsrooms and their audiences are not the allies they should and could be from a “journalism as a service” perspective.

A more detailed analysis distinguishes be- tween internal and external gaps. For example, a print-focused content management system would be an internal gap, a dismal performance among users age 25 to 34 an external one. Participants are encouraged to switch from the “balcony” perspective to the “dance- floor” perspective and back again. With the gaps analysis, honest self-assessment is critical. Ideally, every member of the team shares his or her view, comparing notes leads to meaningful discussions. The more gaps teams identify, the better they can monitor progress later.

The second one of the longer lists will stay with the teams as well, and it requires equal honesty: assessing assumptions versus knowledge. Many business decisions are taken based on assumptions and gut feeling, not based on evidence and knowledge. Examples for assumptions are: “Our audiences enjoy our investigative sports coverage,” “Our onboard- ing process is frictionless,” “Our customers

are willing to pay 9.99 euros per month.” In this exercise all these assumptions need to be rated on a scale from 1 (barely know) to 4 (full certainty). This sounds a bit like tedious work but also helps a lot to monitor progress.

Performance-driven change: what will be done, how and what does success look like?

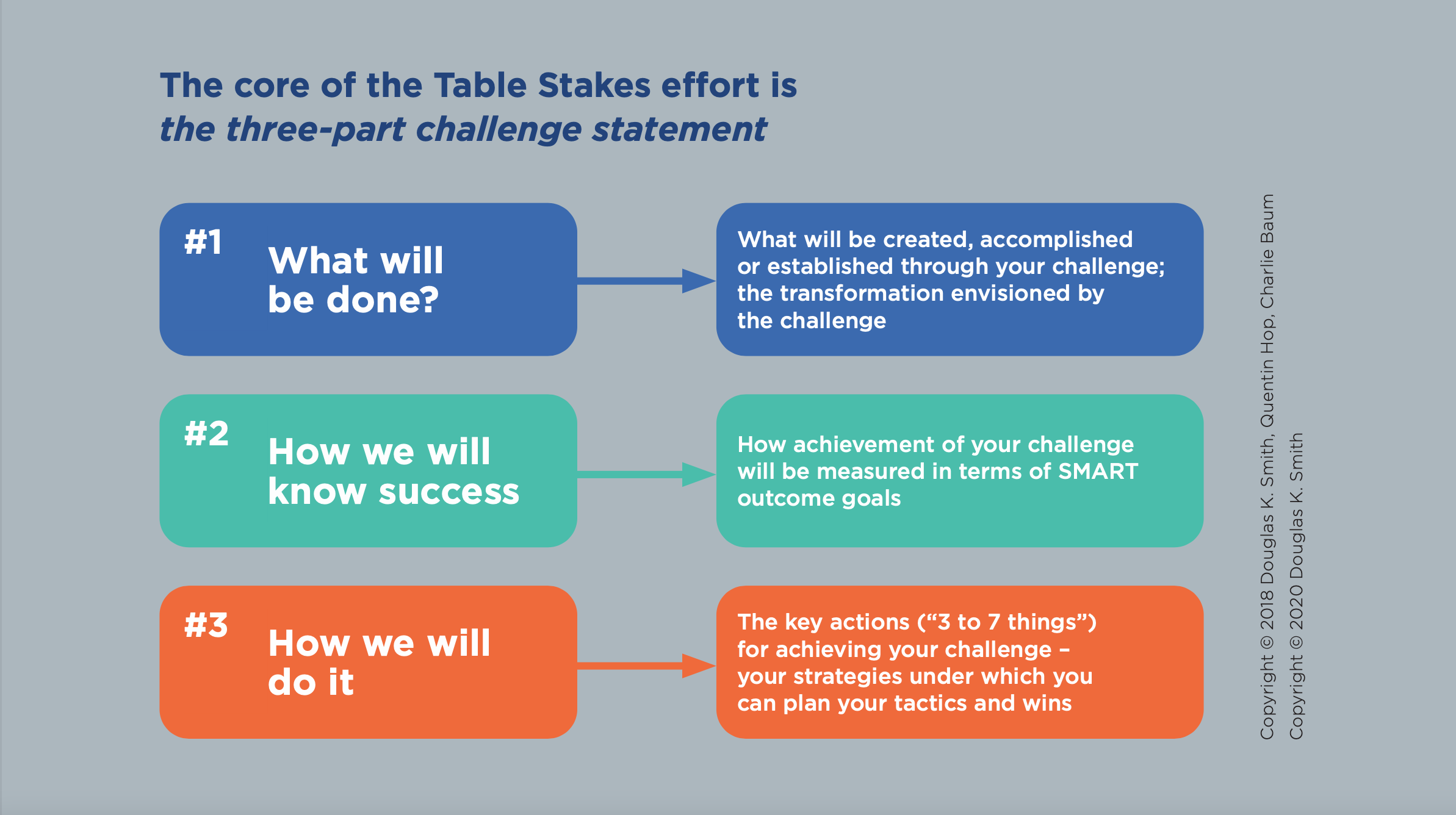

The core of the Table Stakes effort is the three-part challenge statement. This is the carefully crafted guiding vision for the newsroom or publisher. It’s ideally done in clear and telling language, a piece that every participant can quote like the lyrics of a famous pop song.

This sounds like drafting an ordinary mission statement, but the challenge statement is a far cry from those cloudy feelgood-sentences that are predominantly made for marketing materials. The challenge statement includes a vision, clearly defined expectations including finishing line and a set of strategic principles that guide the effort.

“What will be done,” “How we will measure success” and “How we will do it” are the three parts that leave no excuses. Done or not done? That should be easy to clarify in the end. And once it is done, you’d better come up with the next challenge already.

“What will be done,” this can be something like: “We will build sustainable, economically viable relationships with people in our region by being their trusted ally. We will help them navigate their daily lives and responsibilities as citizens by providing them with first-class information and spaces to communicate.” The criteria for measuring success could read something like: “We will triple our number of digital subscriptions to x until the end of 2021.” And “how we will do it,” will surely include something like: “Producing sought after products for existing and new audiences, providing a first-class user experience, fine-tuning and monitoring the entire subscription experience ...” It is important for the challenge to be ambitious yet attainable and understood by every- one in the company.

The “how we will do it” part is the hardest because we are talking strategy here. And the strategy is different from tactics. It bundles the small steps into the overall direction the journey is headed. Teams might have a hard time distinguishing strategy from tactics. But identifying the big picture is important to make sure that tactics feed a bigger goal. A helpful exercise is constructing a strategy tree. It starts with the vision as a starting point, the stem everything emerges from. The strategies are the major branches, and tactics are the little twigs that spring from the branch- es. Tactics that don’t connect to a strategy (branch) are useless, using the image of the tree, they are deadwood. Strategies that don’t connect to a vision are not rooted in the ground, they will lack nourishment. To complete the home- work, every tactic should have a clear numerical goal plus time stamp attached to it.

Remaining focused, overcoming obstacles, whatever they may be

There are three things about Table Stakes that make a big difference to other programmes: First of all, it puts quality journalism front and centre. This is good news to all seasoned journalists who have been a bit wary about digital transformation since they feel this inevitably involves clickbait and “giving away great content for free.” Letting them know that their precious work is at the core of the effort will certainly help to win some of them over. One can fill days with discussions about the true meaning of “quality journalism.” It suffices to say here that it involves the honest effort to research and provide accurate, timely and comprehensible information that is independent of interests and meets ethical standards, but at the same time captures audiences’ interests and serves their needs.

Second, Table Stakes has a strong focus on results, defined as measurable outcomes. While every transformation effort starts with activities, many just get stuck there or barely make it to the output stage. Myriads of meetings result in plenty of papers, concepts, project plans, new hires and teams, huge restructuring ventures – and fall short of showing sizable outcomes and impacts. Table Stakes forces teams to analyse every action that is taken along clear categories: Is this just an activity, is this an output (like a new dashboard or different newsdesk setup), or does it produce an outcome (like new subscribers, additional revenue)? Or can you even attach an impact to it, like a new community centre or a cycle high- way being built because of the relentless exploration and coverage of audiences’ needs? In Table Stakes lingo, this is called the RAOOI evaluation: Is what you are doing just allocating resources (R), engaging in activities (A), producing outputs (O), or is it about outcomes (O) and impact (I)? This clear focus on results prevents teams from falling into the “shiny new things”-trap many digital transformation efforts get stalled at – cool new technology bought to impress, but leading to no change in outcomes.

Third, Table Stakes is pragmatic. It takes into account the resources and people that are there instead of planning for a perfect world that doesn’t exist. This is reflected in two tools in particular. First of all, there is the power/opinion matrix. Bluntly put one could call it a map of friends and enemies, but it should be more detached from the emotional baggage this terminology implies. The power/opinion map classifies every person or group who is needed for a particular challenge along two axes. One is: are they important for the success of the challenge, or can their role be neglected? The second is: how favourable are they to the effort? All those need- ed are then classified as favourable, wafflers, opponents and “don’t know.” If a team finds plenty of names in the box where favourable and important meet, the challenge is likely to succeed. If too many are grouped in the box of “important opponents,” it might be time to adjust the challenge. And with lots of “wafflers” and “don’t know,” the main task is lots of communication, ideally backed up by early wins.

Note that an “opponent” is not a bad person, she or he might have good reasons for being sceptical. Maybe they feel threatened and are afraid of losing privileges. But before wasting too much energy on winning them over, ignore them, if possible. They might hop on board once they see an opportunity to become part of a winning team.

To produce early wins, another matrix is need- ed: the high/low impact and easy/hard to implement matrix. Possible actions can be grouped accordingly. And it doesn’t need much reflection to get started with the stuff that is easy to implement while promising a high impact – the so-called low hanging fruit. Everything that is hard to implement and doesn’t promise too many gains, well, forget about it for now.

Ignoring and stopping to do things that consume too much energy and don’t lead far enough is an important part of Table Stakes: It is critical to decide what to do, of course. At the same time, it is vital to figure out what not to do any longer. Resources are always finite, and focus is essential.

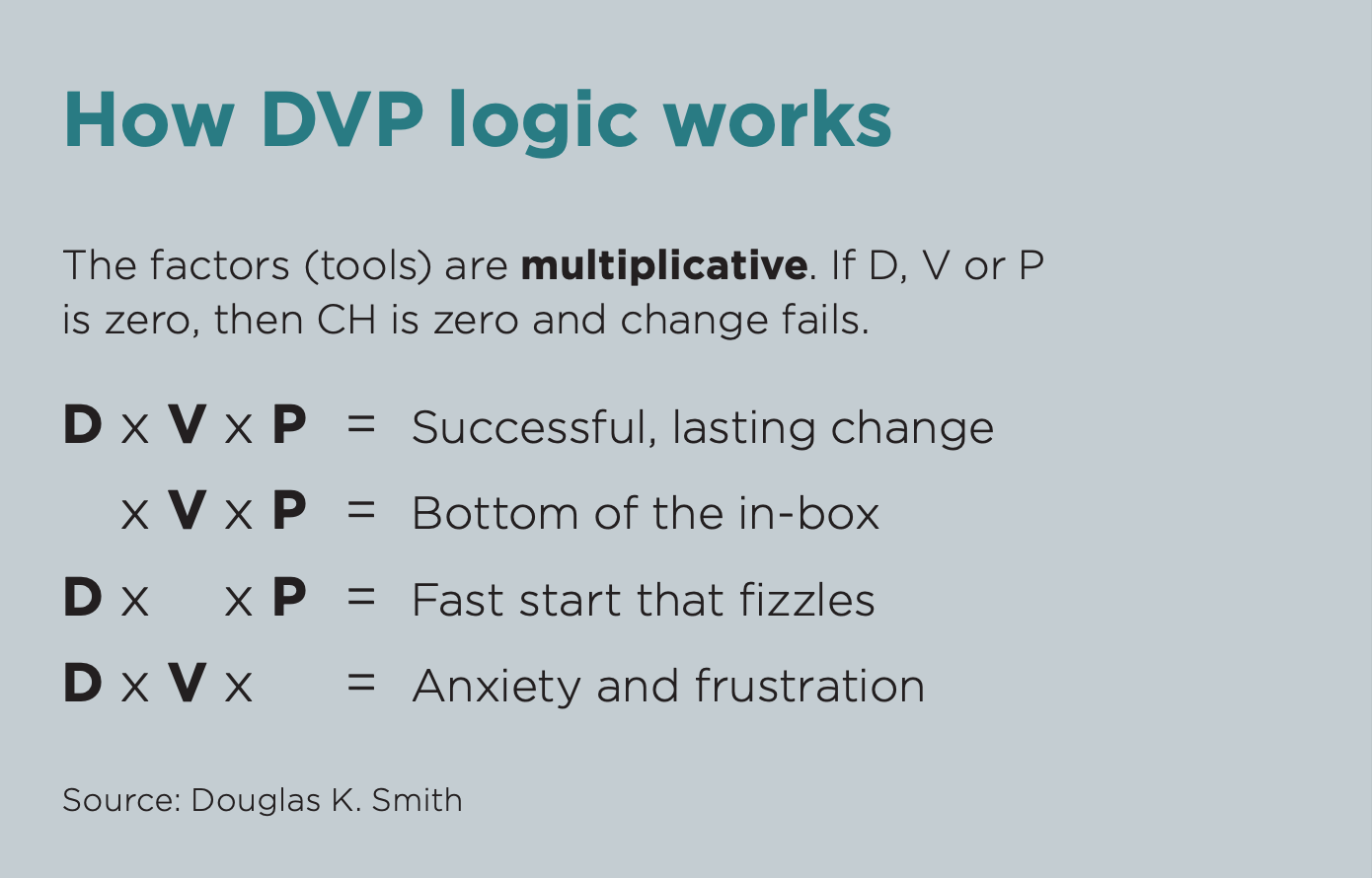

It is possible to analyse the likelihood of success. While there is no magical formula that produces results, the D x V x P formula of lasting change can tell you a lot about what’s missing in your effort. “D” stands for dis- satisfaction, “V” for vision, “P” for processes. All three are multiplicative, this means – remember mathematics – that if one of the parts is zero, the result will be zero.

If there are a vision and processes but no dissatisfaction with the status quo, the “why” is unclear and the venture will take a back seat to other efforts. If there are dissatisfaction and a vision but no processes, teams will get confused and anxious, because they don’t understand the “how.” And if there are dissatisfaction and processes but no vision, no one grasps the “what.” Journalists are skilled at asking all these questions and coming up with the answers. That’s another reason why change management with Table Stakes should hit very close to home.